Beyond Words: Hilyas in Islamic Calligraphy

Exploring the Artistic Expressions that Capture the Physical and Spiritual Essence of the Beloved Messenger in Islamic Tradition.

The term "hilya" (Arabic: حلية, plural: ḥilan, or ḥulan; Turkish: hilye, plural: hilyeler) encompasses a visual representation in Islamic Art and a religious category within Ottoman-Turkish literature. Both aspects detail the prophet Muhammad's (pbuh) physical attributes. The term "hilya" itself translates to "ornament."

These expressions find their roots in the discipline of shama'il, which involves the examination of the Prophet Muhammad's (pbuh) appearance and character based on hadith accounts, with a notable work being Tirmidhi's al-Shama'il al-Muhamadiyyah wa al-Khasa'il al-Mustafawiyyah (The Sublime Characteristics of Muhammad). These compositions typically include descriptions of the Prophet's physical features, character traits, and other attributes, serving as a form of visual praise and veneration.

The most common Hilya text written detailing the attributes and traits of the Prophet comes from Ali (ra). According to Ali ibn Abu Talib (ra), in his depiction of the Prophet (saw), he would express:

‘He was neither excessively tall, nor short, but rather was of a medium stature among (his) people. His hair was neither extremely curly nor straight, but rather wavy and flowing. He was neither corpulent nor was his face completely circular, but it was slightly rounded. (His complexion) was fair with some redness. His eyes were very black, his eyelashes were long. His joints were large and his shoulders broad. He was smooth-skinned; a thin line of hair ran from his chest to his navel. His hands and feet were full-fleshed and sturdy. He walked with vigour, as though descending from a height. When he turned to look (at someone or something), he would turn with his whole person.

Between his shoulders was the Seal of Prophethood, and he is the Seal of the Prophets. His heart was the soundest and most generous of hearts. His speech is the most truthful of speech. He was the gentlest of people and the kindest of them in companionship. Whoever saw him unexpectedly would be awe-stricken. Whoever came to know him would love him. Whoever described him would say, “I saw neither before him nor after him anyone like him”’.

Historical Background:

The tradition of creating Hilyas dates back to the early centuries of Islam, when Muslims sought various ways to express their love and admiration for the Prophet Muhammad. The practice gained prominence during the Ottoman Empire, especially in the 17th century, when the Ottomans developed a unique style of Hilya as an art form. At the end of the 17th century, hilyas in their current forms were first written by the renowned calligrapher Hafız Osman in a specific shape and on a treated paper to be hung on the wall. And firstly, thuluth (sometimes muhaqqaq for the Basmala) and naskh scripts were adopted. At the end of the 18th century, Calligrapher Yesari Mehmed Es'ad Efendi also started writing the hilyas with taliq script; this style continued after him.

During this period, skilled calligraphers and artists were commissioned to create elaborate and decorative representations of the Prophet's qualities. The Ottoman court played a significant role in promoting the production of Hilyas as a means of fostering religious devotion and as a form of cultural expression.

Components of Hilya:

Physical Description: Hilyas often include detailed descriptions of the physical appearance of the Prophet based on various hadiths (sayings and actions of the Prophet) and historical accounts. This might include details about his hair, eyes, complexion, and other distinguishing features.

Moral and Spiritual Attributes: Hilyas also highlight the moral and spiritual qualities of the Prophet Muhammad. This could include descriptions of his kindness, compassion, humility, and other virtuous characteristics.

Calligraphic Styles: The text of a Hilya is typically written in an intricate and aesthetically pleasing calligraphic style. Different scripts, such as Thuluth or Naskh, are often used to enhance the visual appeal of the composition.

Decorative Elements: Surrounding the text, Hilyas may feature decorative elements such as floral patterns, geometric designs, and other embellishments. These elements add to the overall beauty of the composition.

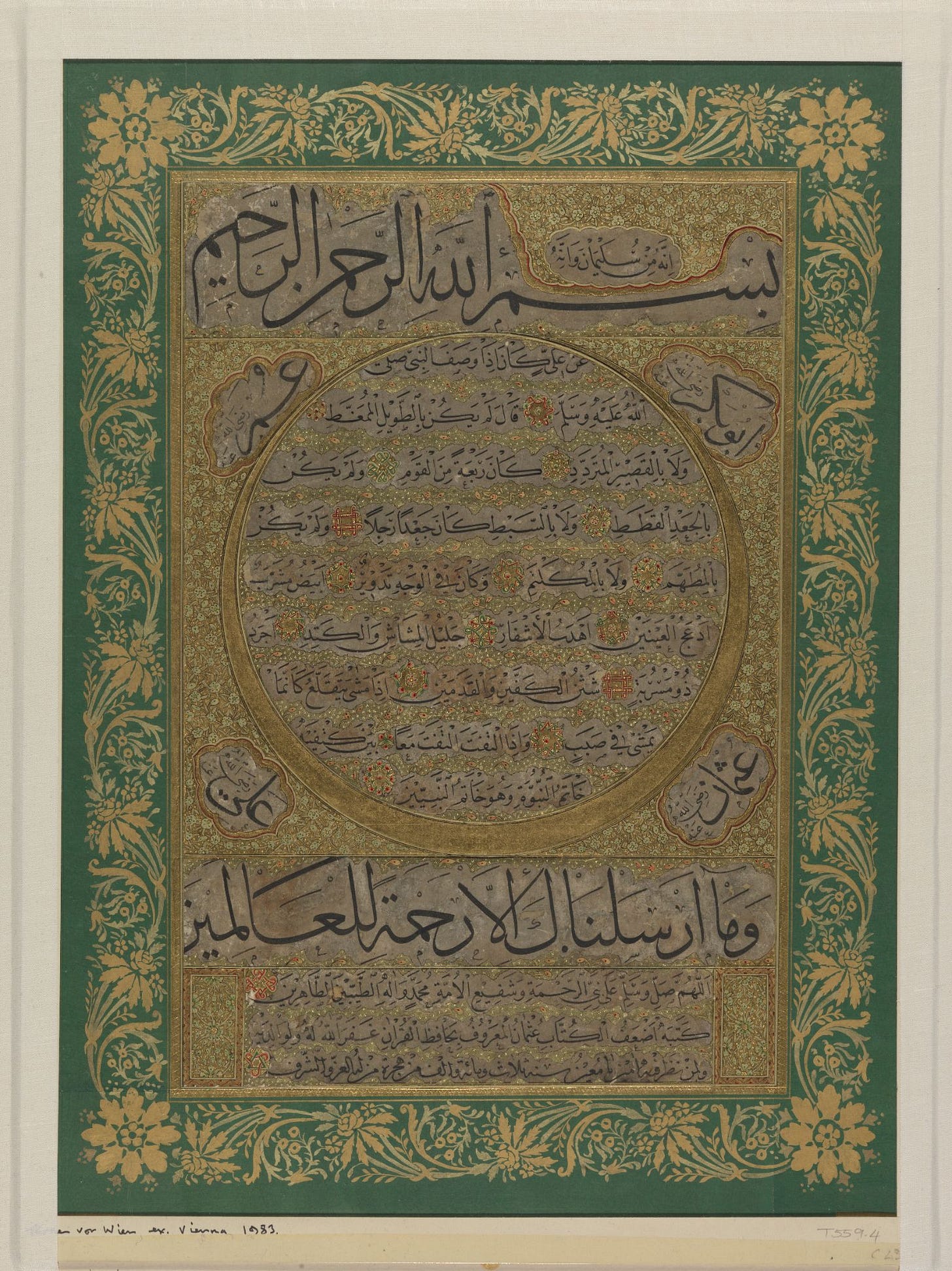

Let’s analyse a conventional hilya design, with their Turkish names in brackets:

Heading: It is essential to inscribe the Basmala in this top section.

Central Portion (Göbek): A significant part of the Hilya text is incorporated into this region, allowing for arrangements in circular, oval, or even rectangular configurations.

Crescent Design (Hilal): There is no obligation to adorn this part with gold or gold-themed motifs; it can be preserved as the central focus. Given Prophet Muhammad's role in illuminating the world, symbolized by the sun and the moon, the decorative piece features the formation of the sun at the center, encircled by the crescent. The outer area of the crescent, completing the rectangular shape, constitutes the most elaborate section of the ornamentation. Within this space, the initial four caliphs (Rashidun) are sequentially positioned:

Abu Bakr (c. 573–634; r. 632–634)

Umar ibn al-Khattab (c. 583–644; r. 634–644) – often known simply as Umar or Omar

Uthman ibn Affan (c. 573–656; r. 644–656) – often known simply as Uthman, Othman, or Osman

Ali ibn Abi Talib (c. 600–661; r. 656–661) – often known simply as Ali

In place of the four caliphs, the other names carried by Prophet Muhammad (Aḥmad, Maḥmūd, Ḥāmid) can sometimes be written. Besides the four caliphs, some hilyas include the names of the ten companions who have been promised with paradise, known as the "al-ʿashara al-mubashshara".

Verse: An ayat from the Qur’an related to the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) is written in this section. The most commonly used one is, "We have sent you as a mercy to the worlds" وَمَآ أَرْسَلْنَـٰكَ إِلَّا رَحْمَةًۭ لِّلْعَـٰلَمِينَ (Surah Al-Anbya, Verse 107).

Sometimes, "And you are truly ˹a man˺ of outstanding character. وَإِنَّكَ لَعَلَىٰ خُلُقٍ عَظِيمٍۢ" (Surah Al-Qalam, Verse 4), or

"O Prophet! We have sent you as a witness, and a deliverer of good news, and a warner," ٱلنَّبِىُّ إِنَّآ أَرْسَلْنَـٰكَ شَـٰهِدًۭا وَمُبَشِّرًۭا وَنَذِيرًۭا (Surah Al-Ahzab, Verse 45) can be written in this part instead of the initially mentioned verse.

Skirt: It refers to the continuation of the hilya text and the prayer section. The calligrapher who writes the hilya at the end also adds his signature and the date he wrote it.

The empty spaces on either side of the skirt section (10, 11) are called "armpits" (koltuk), and decorative motifs are placed in these areas.

Significance in Islamic Calligraphy:

Spiritual Remembrance: Hilyas are a visual means for Muslims to remember and venerate the Prophet Muhammad. Displaying or reading a Hilya is considered an act of spiritual remembrance and a way to draw closer to the teachings and example of the Prophet.

Artistic Expression: Hilyas represent a unique form of artistic expression within Islamic calligraphy. The combination of intricate calligraphy, detailed descriptions, and decorative elements showcases the rich artistic heritage of the Muslim world.

Hilya by calligrapher Mehmed Es'ad Yesârî in taliq script. Source:. Cultural Heritage: The tradition of creating Hilyas has been passed down through generations, contributing to the cultural heritage of the Islamic world. The art form has evolved, with different regions developing their styles and variations.

In summary, Hilyas play a significant role in Islamic calligraphy by combining visual artistry with textual descriptions to honour and celebrate the physical and moral attributes of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). The tradition has historical roots in the Ottoman Empire and continues to be a cherished form of artistic and spiritual expression within the Islamic world.